Hear y’all, hear y’all! While the Scout has been bopping along mostly uninterrupted, I’ve been MIA for about two months. But now I’m back—not particularly improved after a vacation—and excited to dig back into the things that make us tick.

Let’s get into it.

On Our Minds

Incarceration.

I’ve been thinking about writing this one for a while, honestly, but have been too exhausted to do it. For those of you who don’t know (and I’m assuming that’s most of you), most of my actual day job focuses on civil rights for incarcerated people. (Yeah, that’s where we’re going with this. Strap in.) Since moving to West Virginia in early 2022, I have spent time in every jail and a good number of the prisons in West Virginia.1 Personally, I think everyone who wants to have an opinion about carceral facilities in the US should have to at least visit a jail or prison, but since I know that’s not in the cards for many of you, you’re getting this instead.

There’s a lot that could (and has, by people much smarter and more thoughtful than me) been said about the origins and history of mass incarceration in the United States, and about how this system was designed to keep rich and powerful (and white) people rich and powerful, and everyone else in their place. Because I don’t have a semester’s worth of courses or unlimited words here, I’m going to talk about the here and now of a particular facet of mass incarceration in the US, and in West Virginia in particular.2

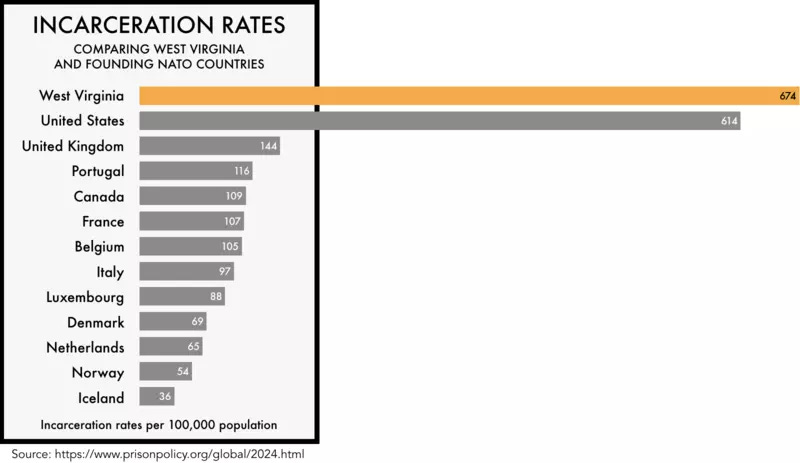

First things first. We lock up a lot of people in West Virginia. In fact, if West Virginia were a country, its incarceration rate of 674 people per 100,000 would fall between Cuba (794 per 100,000) and Rwanda (637 per 100,000).3 In comparison to what America commonly thinks of as our “peer” nations (i.e., Western European countries), both West Virginia and the United States as a whole lock people up at a staggeringly high rate.

At any given time, there are around 11,000 people locked up in West Virginia.4 Although West Virginia’s population is only approximately 3% Black, Black folks make up approximately 14% of the state’s incarcerated population, following the national trend of locking up black and brown people at a disproportionately high rate.

I could go on but, again, others have done that better than I ever could. Instead, I want to talk about the purpose of jails and prisons: what we want them to do and what they actually do. (Spoiler: these are not the same thing.)

What we want prisons to do: We want prisons and jails to make us safe. I think that’s a fairly basic and understandable desire. When bad things happen—when people are hurt or things are damaged—we want there to be a response that makes us feel safe from continued danger. Incarceration of the (alleged) wrongdoer seems to promise that safety. If the evildoer is locked away from society, they will do no future damage to us or our communities.

We also want the wrongdoer to be punished. Again, this is something that, as a gut response to damage or harm, is understandable. It also ties in with the American understanding of “justice:” the evildoer is locked away and the victim is saved (or at least avenged). The dragon slain, the princess rescued. All is well in the kingdom once more.

These desires in and of themselves are entirely human. Who among us doesn’t want to feel safe, or want our basic sense of fairness fulfilled? These desires are not, however, particularly forward-looking, nor are they a strong basis for public policy.

They’re also not what prisons actually do.

What prisons actually do: Harm.

I believe this with every fiber of my shriveled little soul, and the data backs me up. Our system of mass incarceration harms everyone touched by it: the people who are caged in our prisons and jails; their families and loved ones; the people who work in these facilities; the communities whose members are stolen away; and us. All of us.

We like to tell ourselves that we are safer because dangerous “criminals” are locked away, and while that sounds like it should be fairly obvious, it’s not true. There are decades of research that show that a higher incarceration rate does not positively correlate to a lower crime rate.5

Higher incarceration rates do positively correlate, however, to: destabilization of families; homelessness; poverty; housing and job discrimination; reincarceration; intergenerational incarceration; and even increased rates of crime.

Prisons are terrible places. Terrible. This is something I didn’t know until I started spending a good amount of time in them, speaking to people who are caged there. Even where the carceral experience is not made intentionally worse by prison staff, American prisons are designed to strip away identity, agency, control, and humanity from the people caged there. These places take and take and take and, for many, when they have served their state-mandated sentence, they are left with nothing.

Even when people are released, they’re not free, not really. Formerly incarcerated people are not a protected class in America, which means that many employers, housing providers, banks, and others are free to discriminate against them because they have been in prison. Think about all the job applications you’ve submitted that ask if you have a criminal history. Think about loan or rental applications. The problems don’t end there. Many states impose restrictions on SNAP benefits for people convicted of drug-related felonies. Certain felony convictions can negatively impact your ability to qualify for Section 8 housing vouchers. Though we pay lip service to the idea that, once people complete their sentences, they can rejoin society, but the reality is that, for many formerly incarcerated folks, there is no return. Exclusion from the benefits of society that so many of us take for granted increase homelessness; joblessess; and make it more likely that people will end up in a jail or prison again.

Outside of the incarcerated folks themselves, mass incarceration sucks money from their families, in the form of ruinous phone rates and the huge amount of money families sent to loved ones to pay for commissary items. Children are deprived of parents, parents lose their children, and friends and family are left with gaping holes.

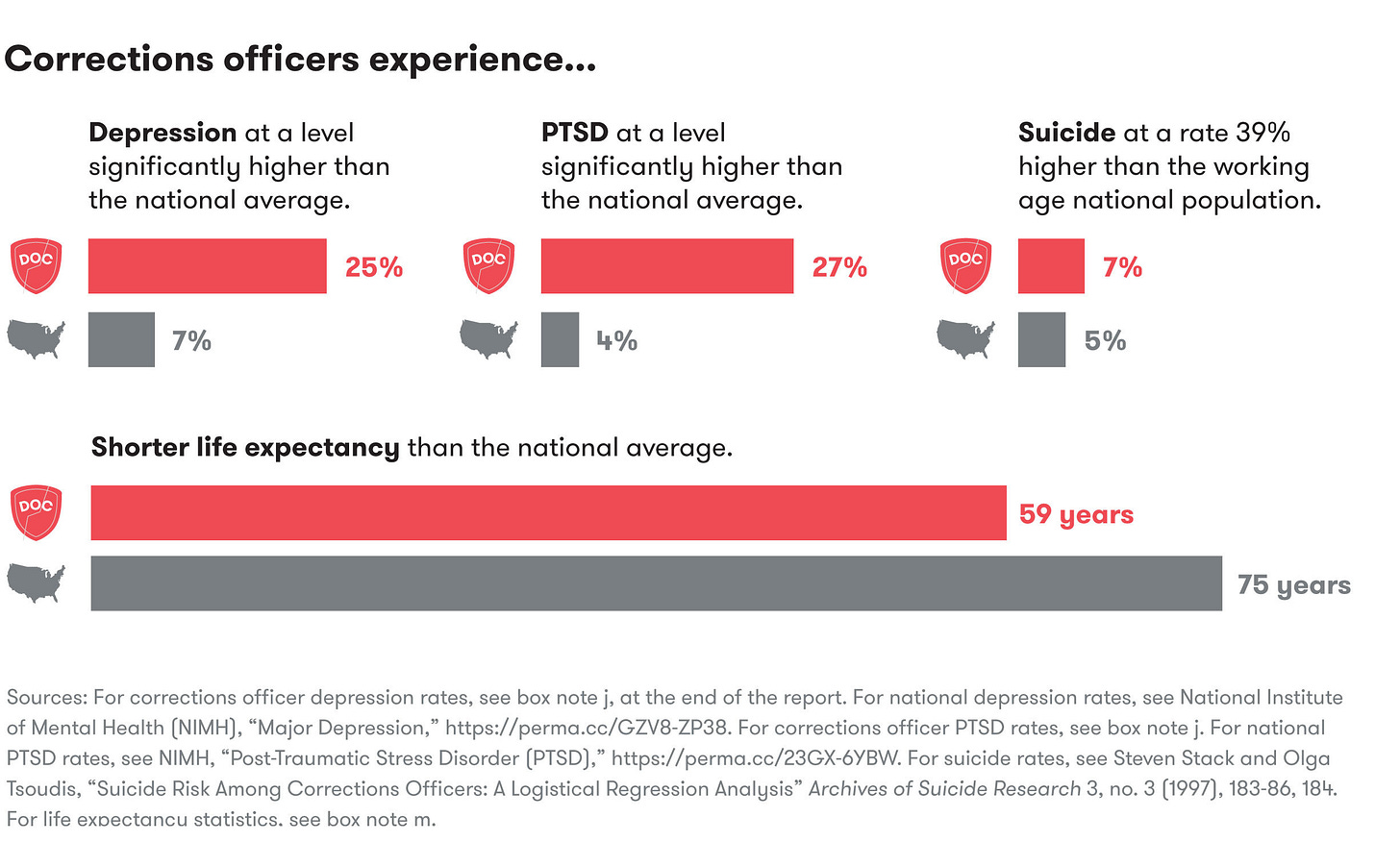

Mass incarceration is also damaging to people who work in prisons, with research showing that correctional officer “suffer from PTSD and commit suicide at rates much higher than law enforcement staff in other agencies.” Officers are exposed to routine, mundane violence, and spend their days working in a facility where they are expected to dehumanize the incarcerated folks caged there.

Finally, mass incarceration harms us. Yes, even those who have never even seen a prison, who don’t know a single soul who has been there or worked there. It harms us when our tax dollars go to fund locking up people for the crime of being poor or having a substance use disorder. It harms us when our governments prioritize prison funding over community hospitals or public education or infrastructure. It harms us when we accept a world where prisons act as warehouses for people the state has decided are simply too much trouble to help. It harms us when we accept that the state can commit violence against us—because incarceration is violence.

This is what prisons do: they harm us. All of us. And I’d like to suggest that it’s time to place the American way of prisons and mass incarceration into a systems thinking approach: the purpose of a system is what it does.

Forget intentions, forget what we want prisons to do. The purpose of a system is what it does.

Harm.

In Our Community

On Tuesday, July 16, Morgantown City Council meetings starting at 7:00 pm. I hope we're all used to the Spruce Street location by now, but if not, there’s your reminder. Here is a link to the agenda. Looks like it is mostly unfinished buisness except for a budget reallocation so this meeting might only contain administrative responsibilities.

Also on Tuesday is the monthly Silent Book Club at AntiqiTea House at 6:00 pm. Bring a book, grab a snack, and enjoy some parallell socialization with fellow readers.

On Wednesday, July 17, Professor Stuart Walsh of WVU will discuss his book Hornyheads, Madtoms, & Darters in a Local Author Spotlight at the Aull Center at 6:30 pm. Our very own Monkey Wrench Books will be on hand with copies once you’ve been captivated by the Q&A.

On Friday, July 19, the West Virginia Botanic Garden is hosting Moth Night, led by moth enthusiast Tucker Cooley. Like moths? Who doesn’t? Moth Night starts at 8:30 pm and is $15 for non-WVBG members. Get tickets here!

Also kicking off this Friday is Bike Bash WV 2024. Bike Bash runs July 19-21 and celebrates over 50 miles of trails at Big Bear Lake Trail Center in Bruceton Mills. When I last checked there were still a few slots left!

Finally, on Saturday, July 20, the City of Morgantown and Morgantown Magazine kick off their Don Knotts Festival at the Morgantown Metropolitan Theatre, which will run through July 24. The Metropolitan will screen films featuring Don Knotts, and on the schedule for Saturday are The Incredible Mr. Limpet and The Ghost and Mr. Chicken.

The Kitchen Sink

Books: I was on vacation for about two weeks, so I’ve actually managed to read a decent amount. Most recently I finished Prophet Song by Paul Lynch. This isn’t some unknown gem: Prophet Song won the 2023 Man Booker Prize and has been generally lauded. If you want a book about how the world ends ever so slowly before it ends all at once, this is for you. If a modern day Ireland slowly slipping into authoritarianism before breaking down completely hits a little close to home for you right now, well, maybe not for you.

On a lighter note, I also recently read Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch, by Rivka Galchen. Historial fiction that also manages to be a very funny excoriation of moral panics, the story follows Katharina Kepler, who is accused of and ultimately tried for witchcraft. Before this book I had no idea that Johannes Kepler’s mother (yes, that Johannes Kepler) was actually accused of and imprisoned for witchcraft. The more you know.

I normally force a few more of my opinions on you in this section, but I’ll be honest, it’s time for me to watch the end of the Argentina-Colombia match, and I’ve hopefully given you quite enough to chew on for the day.

Onwards and upwards!

- Lesley & the Scout crew

What’s on your mind? What civic or cultural events are on your radar this week? What would you like to hear about in future newsletters? We want to hear from you in the comments or at morgantownscout@proton.me. Help us build the Scout community!

But Lesley, you say, what’s the difference between a jail and a prison? Aren’t they just two words that mean the same thing? Why, thank you for asking, gentle reader. While the words are often used interchangeably, jails and prisons are different. Jails are designed to house individuals who have been arrested or charged but have not yet been found guilty and sentenced (commonly referred to as pre-trial detainees). Prisons are designed to house individuals who have been found guilty and have been sentenced. In West Virginia, you will often find people who have been convicted but not sentenced, as well as people who have been sentenced to shorter terms of incarceration (often for misdemeanors) who are also held in the jails, but for the most part, a simple way to think of the jail/prison distinction is that jail is for people who haven’t been convicted, and prison is for people who have been convicted and sentenced. For convenience here, I’ll use “prisons” to talk about carceral facilities more generally.

At some point, I or someone else with tackle other aspects of mass incarceration, including most excitingly abolition. But that is not this day.

A lot of the numbers in this post are pulled from the incredible Prison Policy Initiaitve, which produces some of the most comprehensive and comprehensible reports, briefings, and graphics and modern mass incarceration in the United States.

This number includes people incarcerated in the many federal carceral facilities in West Virginia.

I’ll also point out that many if not most crime rate statistics do not include the rate of crimes in jails and prisons. Gee, I wonder why.

Thank you for writing this. I hope this is part of a series that dives into this deeper and how we can make change!

1. PREACH!

I have extensive work with people on both sides of the fence, and have taught Intro to Corrections at Fairmont State. I can tell you from a "boots on the ground" perspective that you are absolutely right. While the Federal system has some advantages that WV does not have as far as treatment and education and support, it and the State has a LONG ways to go. There's so many issues including our own mindset as a State and nation towards the role and function of corrections.

As a disclaimer, yes, I've worked inside maximum security and I am thankful that there are some people who will not see daylight ever again.

Having said that, corrections is a failed system, the end result of a whole spider web of failed systems. However, I am also a bit of an optimist. I've seen success stories with my own eyes. There are resources being funded by State and Federal sources that can actually work. I believe we may be slowly getting the message, but as stated before, we still have a long ways to go.

I look forward to continuing this much needed conversation with everyone here!